When the Epic E1000 was finally certified in the spring of 2020, there was much celebrating across the aviation world. Epic Aircraft expended a lot of time and energy getting the E1000 certified and into production (more information on that journey here and in Flying Magazine here).

The airplane is amazing. In the single engine, 6 seat turboprop market, it easily blows away the competition. With it’s 1,200 SHP PT6-67A, it has double the horsepower of the M600 (600 SHP), and 350 more horsepower than the TBM 940 (850 SHP). It’s 60 KTAS faster than the M600 and, even though the TBM can keep up (both airplanes have equal top cruise speeds of 330 KTAS), the Epic E1000 can carry a payload of 1,024 pounds with full fuel, while the 940 can only carry 584 pounds with full fuel. The TBM carries about 15 minutes more of fuel, but to me, that’s pretty negligible.

Did I mention climb rates? The E1000 climbs at an average of 1500 FPM at Vy (it’s capable of 4,000 FPM), making it to 25,000 feet in 10 minutes. The TBM climbs at 1000 FPM, taking 13 minutes to climb to the same altitude, while the M600 settles in at about 800 FPM, reaching FL250 in 21 minutes.

If you expand the comparison to include the Pilatus PC-12, the two airplanes have 1,200 SHP, but the Epic is 50 KTAS faster and they both have about the same weight carrying ability.

In the most important arena, price, the E1000 is around a million dollars cheaper than the TBM 940.

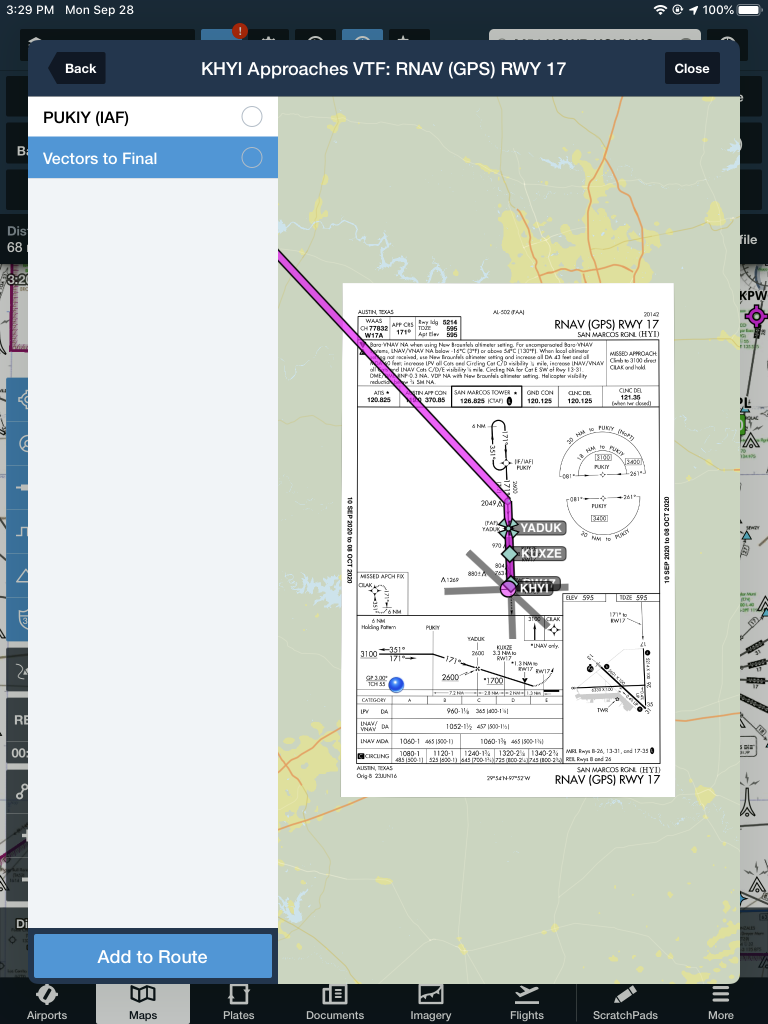

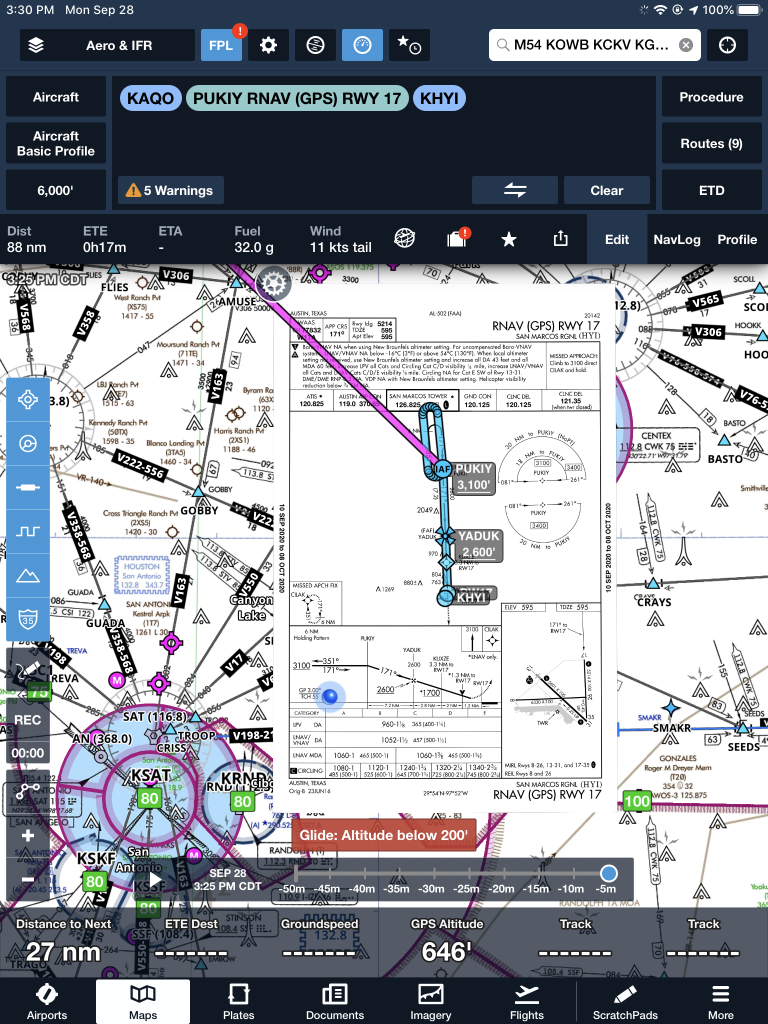

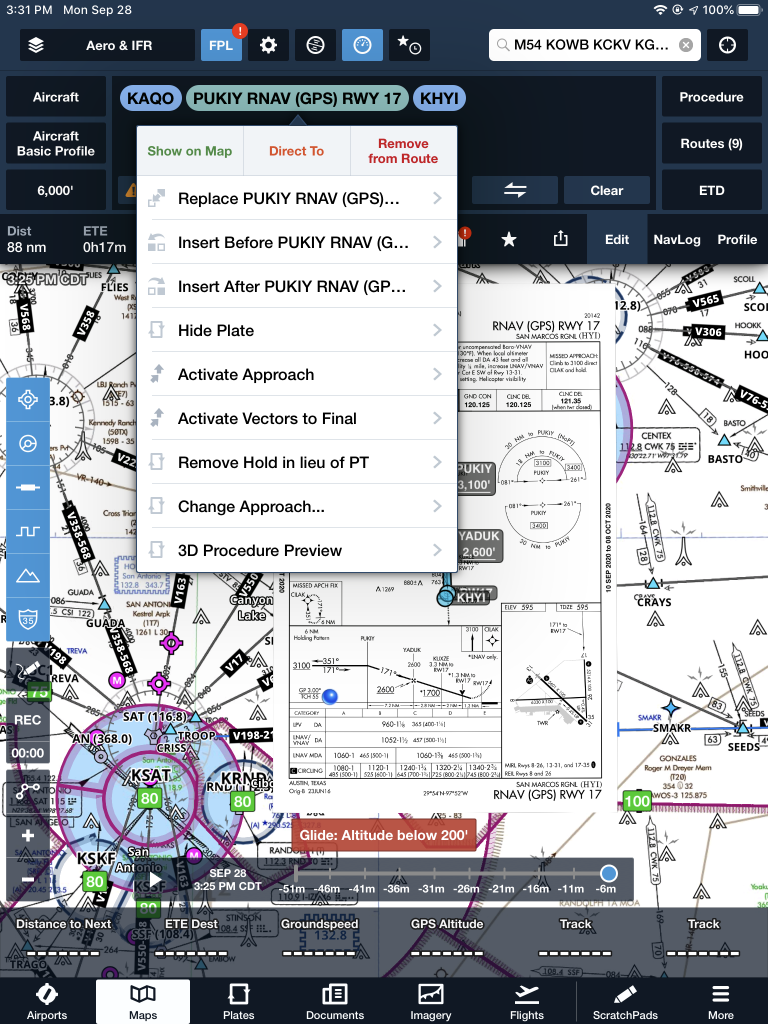

The one drawback to the Epic E1000 that immediately was noticeable was the autopilot. Epic originally installed the STEC 2100 autopilot to pair with the G1000 (and later the G1000 NXi). Epic decided to stick with the STEC 2100 through certification for the plane since that autopilot was on all of the E1000s paperwork going through all the levels of FAA approval. To change to the GFC 700 during the certification process would have been a massive undertaking that probably would have delayed certification.

The STEC 2100 is a good autopilot, but, as any G1000 pilot can tell you, the lack of integration between any STEC autopilot and Garmin panel leaves some to be desired. Not all the bugs talk, which often requires dual data entry, which can lead to forgetting to do both the bug and the autopilot when things get busy. Hello, altitude deviation.

The goal for Epic was never to leave the STEC autopilot in the airplane. The first E1000s were rolled off the line with the STEC, but Epic didn’t take long to change the autopilot to the much more integrated Garmin GFC 700. That took place this winter (2020), and the E1000 received it’s first upgrade, with Epic dubbing the airplane the Epic E1000 GX.

I expect the innovators in Bend, OR, where Epic is based and where tons of innovation in aviation happens (Lancair/Columbia started in Bend while RDD is based there as well), to quickly come out with more avionics upgrades for the airplane. I wouldn’t be surprised to see a G3000 version at some point, complete with auto throttles and the new Garmin Autoland. Epic would be smart to follow in the steps of Daher and offer two models, one with the G1000 and one with the G3000 (the TBM 910 has the G1000 NXi while the TBM 940 has the G3000).

I have yet to fly in an Epic E1000, but I would certainly jump at the chance to do so. Someone asked me yesterday what airplane I would buy if I had a blank check. With the GFC 700 now in the Epic, it would absolutely be the E1000 GX.