My first chief flight instructor had an addage he would impart to his flight instructors when we began working at that flight school. “Pitch + Power = Performance” he would tell us. Then he’d glare at us and follow up with, “nobody teaches that right, so make sure your students know it.”

Now, having been a CFI for seven years, I would tend to agree with him. I have moved on from doing mostly primary training to transition training. Transition training is taking someone who is already a pilot and teaching them how to fly a different type of airplane. In jets, you get a type rating. In piston engine airplanes, there is no FAA requirement to go through any type of extra training as long as you are rated in category and class (eg. single engine piston). But, insurance companies know that Mr. Fresh Private Pilot can’t just hop from a Cessna 172 into a Cirrus SR22 or a Bonanza, so they require transition training before insuring those pilots.

What did my chief instructor mean when he imparted his wisdom? He was speaking about a particular phase of flight, the final approach phase, regardless of whether it’s a VFR approach or an IFR approach. The pitch of the airplane and the power setting of the airplane have to be utilized together to achieve the proper speed and descent rate (performance).

VFR

On the final approach leg of a VFR pattern, most piston engine aircraft are configured with landing gear down and flaps down in the landing position. This puts the airplane on the back side of the power curve in the region of reverse command. In the region of positive command, in cruise, for example, the more power you add, the faster you are going to go and, if you pitch up, you will go up and you pitch down, you will go down. But, they work together (if you point the nose down, you will accelerate unless you reduce the power); remember, Pitch + Power = Performance.

In the region of reverse command, the pitch controls the airspeed and the power controls your rate of descent, but, again, they work together. Let’s say the airplane is 5 knots above it’s approach speed on final. Initially, the pilot will need to pitch up slightly to bleed off that airspeed. The airplane will want to climb, so as he is pitching up, he’ll need to make a slight power reduction to stay on glide slope.

Alternatively, let’s say the airplane is high, but is on speed. The pilot will make a power reduction to descend to the glide path, but he’ll also need to pitch down to maintain the proper airspeed.

What you don’t want to do is this: if the airplane is high on final, don’t push the nose down to try and get down. This does cause the airplane to lose altitude quickly, but the airspeed increases quickly. With a higher airspeed, the airplane has a lot more energy to dissipate when it gets to the runway, meaning you’ll float longer which can lead to forcing the airplane down or using up too much runway and not being able to get the airplane stopped in time.

IFR

On an instrument approach, you are on the front side of the power curve. When trying to stay on glide slope, the power is controlling the speed of the airplane and the pitch is keeping the airplane on glide slope. This can be a little bit confusing for VFR pilots transitioning to instrument approaches as they are not used to being on the front side of the power curve.

Keeping in mind that Pitch + Power = Performance, let’s put the airplane above the glide slope on an ILS approach. In order to get down to the glide slope, the pitch needs to be lowered as much as needed (it’s always better to pick a pitch attitude to fly and see if it is working to bring the glide slope back to center. If it doesn’t work, pick a new one. Don’t just push the nose down until the glide slope moves) and the power needs to be reduced to maintain airspeed (again, pick a specific power setting). Once the glide slope centers, then the pitch will be raised slightly and the power will need to be increased to hold glide slope and speed respectively.

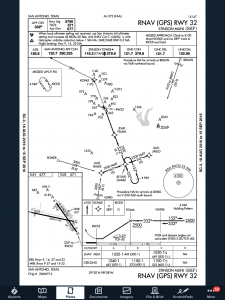

First things first. The first step of an instrument approach briefing is to brief the approach plate. There are a bunch of acronyms out there that instructors tell their students to memorize that only cause confusion instead of helping get the plate briefed. To keep it simple, just work your way across the plate and you’ll get all the information you need.

First things first. The first step of an instrument approach briefing is to brief the approach plate. There are a bunch of acronyms out there that instructors tell their students to memorize that only cause confusion instead of helping get the plate briefed. To keep it simple, just work your way across the plate and you’ll get all the information you need.