The FAA defines personal minimums “as an individual pilot’s set of procedures, rules, criteria, and guidelines for deciding whether and under what conditions to operate (or continue operating) in the National Airspace System.” Have you actually given thought as to why we choose the personal minimums we do? From the beginning of initial pilot training, weather minimums were established for day-to-day training and during solo flight. I didn’t realize it at first, but I later learned these limits were not just an insurance mandate, but these minimums were set at the time to safely operate an aircraft based on my “then” current experience.

So here’s the question: what are your personal minimums and WHY do YOU have them? Do you ever lower or raise your minimums? Are your minimums based solely on your overall experience level or do they take into account other variables such as advanced avionics? For pilots that fly multiple aircraft like I do, can and do your minimums change in regard to category or type of aircraft you are flying? It’s a judgment decision on how you chose your minimums. However, it’s important that time is taken before you strap into the cockpit for each flight to critically think about the different risk factors and variables which may affect your decision for the minimums you choose.

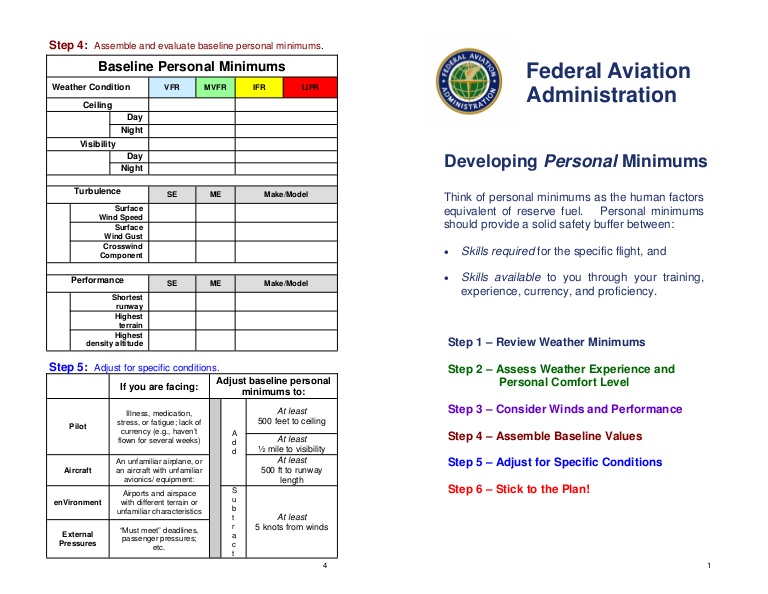

To guide us, let’s try briefly apply the FAA’s Personal Minimums Checklist to see how risk factors might shape what personal minimums or decisions we make for the day. Remember, just because you have been flying with a certain set of minimums one day, doesn’t mean you can’t adjust your minimums to a higher value given an ever-changing situation.

The acronym most pilots have heard is PAVE:

Pilot– We all should be familiar with the acronym IMSAFE associated with this. It addresses variables such as Illness, Medication, Stress, Alcohol, Fatigue, and Emotion. But how do you adjust your personal minimums using this guideline? Have you ever thought about raising your minimums for a training flight if you only got 4-6 hours of sleep, instead of 8? Or if you anticipate a hard IFR flight with a long day, maybe taking a safety pilot to mitigate the chance of a mistake if you’re forecasting having to shoot an approach to your weather planning minimums.

Aircraft– Personally, this is a really important factor for me when deciding what minimums to apply. I often spend a large majority of my time asking myself; is this aircraft properly equipped for the flight? This question goes beyond just looking at the logbook for a properly equipped and legal aircraft. A professional pilot should think further. Am I flying a traditional 6-pack “steam gauge” layout, non-slaved compass card, with a separate OBS gauge for course guidance? What if the aircraft doesn’t have an auto-pilot? What if I’m flying an aircraft equipped with a dual auto-pilot, dual GPS with an integrated glass cockpit? I can comfortably say my personal minimums change depending on the equipment I have available.

A pilot should also look at his/her recency with the aircraft. For example, if you are qualified to fly both airplanes and helicopters, maybe you should choose to have higher personal minimums in one particular airframe or if you haven’t flown that airframe within 30, 60 or 90 days. This is a very important factor for the owner/pilot.

EnVironment– Most of the time, when we think of environment, we ask ourselves, is the weather legal for me to take off and, more importantly, can I conduct this flight safely? Basic flight planning should have taught us to take into consideration crosswind limits, day versus night, and the type of airspace the flight is conducted in. Thought should also be given to how you set your personal minimums in regards to the particular type of environment you might rarely encounter. Flying an approach to your minimums in the flat plains of Texas during the day is one thing, but how would you adjust your weather minimums flying to a new airport, at night, with no moon illumination, in the mountains of Colorado? Could you reduce the risk and adjust your minimums in this scenario with two pilots?

External Pressures – What external pressures are affecting your flight? Passengers, the owner, “get-there-it is”, the desire to impress someone? Although external pressures should never be a factor when conducting a flight, they almost always play a role in your decision whether to conduct the flight or not. For example, a professional pilot gets hired to do a flight and the weather is below their personal minimums. The pilot could be tempted to lower their minimums by 100 feet to take the flight for a paying customer. This scenario plays out every day across the country whether it’s a professional pilot or owner/pilot. It would be foolish not to consider this type of pressure. Always make sure you have a plan if and when you encounter this situation. Planning your flight and having a plan to deal with these potential scenarios ahead of time ensures you stick to your minimums. It can be as simple as telling your passengers, or the owner, well ahead of your flight what your personal minimums are to accept the flight, and to ensure they, or you, have a back-up plan!

Most pilots will never break a hard limitation such as an airframe cross wind limitation, or engine limit, but the chances of breaking a personal minimum are realistic. Think about the last time you went on a diet and broke your plan because you were tempted by your friends or family during an outing. Self-imposed personal minimums can be hard to enforce and we need to acknowledge this as humans. Here are a few techniques that you can use to assist in making a decision using personal minimums and help reduce the influence of external pressures.

Step 1: Sit down with your CFI/CFII and fill out a personal minimums worksheet. Filling one out by yourself is a good start but having an outside objective view will help in making sure your personal minimums are realistic. Remember, it is easy to convince ourselves that we can do something even though we have set personal minimums. Talk with other pilots to see if you have set realistic expectations.

Step 2: Preflight planning must start a few days in advanced. It can be as easy as checking what the forecast might be and looking at the projected route, near-by alternate airports, and various approaches. This can be done quickly and will give you a heads up on whether the flight can be safely conducted or not. By alerting the passengers or owner early enough, alternate plans can be developed. An extra pilot can be added, the passengers can fly commercial, bring along a CFI, or cancel the trip altogether and seek alternate transportation. The main point is the decision was made well ahead of the flight when conditions didn’t look favorable. This helps in removing external pressures and ensures you don’t go below your personal minimums.

Step 3: Never be afraid to ask for a second opinion. Part 135 operators have set procedures for conducting flights which assist the pilots in making decisions. These set procedures help remove external pressures by allowing the pilot to say, “The rules don’t allow for this, or this is how we will conduct the flight!” However, under Part 91, the pilot has to take ownership for all phases of the flight. This is where talking it out with another pilot helps with mitigating external factors and the environment. Ideally, this person should have more experience and be able to talk through the situation. For instance, if I’m flying to a new destination, I often seek the advice from another pilot who’s familiar with the area. They may have key insights into weather patterns, preferred approaches, or hazards to avoid. In certain situations, asking for another pilot’s opinion might be what influences your go/no-go decision! You’ll be amazed how much you can learn just from talking to other pilots.

Step 4: Continue to build your experience and knowledge base. Building experience requires us to push our abilities, and sometimes this may be to the limit. However, this can be done in a controlled training environment or just going out and experiencing it. Get a new license, fly regularly with a CFI/CFII, and always try and take advantage of training opportunities. For example on your next flight from point A to point B, practice hand flying an approach, do a short field landing, a quick steep turn, etc. Quality flight time is always better than quantity. Continue to challenge yourself and try not to become complacent.

Personal minimums are a tool to assist in every pilot’s aeronautical decision making process. Use your personal minimums to guide your final go/no-go decision and remember to stick to the plan. I encourage you to review the FAA’s Risk Management Handbook (FAA-H-8083-2). Appendix B has Sample Risk Management Scenarios and reviewing them will give a better understanding how to apply the techniques discussed to your everyday flying.

Pedro Vargas-Lebron is a King Air 200 and uH-60 Blackhawk Instructor pilot with the Texas Army National Guard. Pedro is a CFI/CFII/MEI both in airplanes and helicopters with over 4000 hours of flight time, half as an instructor pilot.