Ever since I moved out to the Philadelphia area, the Hudson River corridor in New York City has become one my favorite places to fly. It’s hard to overstate the beauty of the city from low over the river. Every time I have a family member or friend come to visit, I try and take them over to see the city from the air.

Each time I fly up the river I can’t believe that we are actually allowed to do so, flying below the tops of the buildings and close enough that you feel that you could reach and out touch them. The draw back to the Hudson River Corridor is that it can be busy, intimidating, and confusing. However, with some reading and preparation, the Skyline flight is easy to do and extremely rewarding.

Having the right weather is an important first step. The second step is try to arrive during ideal lighting conditions. If possible, select a smooth, calm day to make it easier to maintain a track down the correct side of the river. I always try and target arrival at the city around sunset. The view is spectacular any time of day, but having the lights from the city while the sun is just setting gives the best viewing. I’ve also flown over and done the whole flight after dark, which is always spectacular.

The first method of flying the river is to utilize VFR flight following. If the controllers aren’t too busy, they will provide advisories to aircraft that request the Skyline. The nice thing about doing it this way is that the controller will clear you into the NY bravo airspace and keep you above the traffic flying the Skyline in the VFR corridor below. This is the method that I have always preferred as I enjoy the added benefit of the traffic advisories and it’s nice not to worry about position reporting on the radio.

If you want to get flight following, head toward the corridor and request the Skyline route with NY Approach. (Remember to stay clear of the Bravo until you’re cleared in!) Once you’re cleared into the Bravo and approaching the corridor, they will hand you off to Newark/ LaGuardia Tower for traffic advisories over the river. I like to approach from the south and ask for a 180 over the George Washington Bridge. This allows me to fly past the city a second time before exiting the corridor over the VZ (Verrazano Bridge) and heading back toward home.

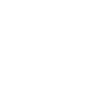

In red is the path I typically fly. I descend to 1400’ and fly toward the APPLE intersection picking up the shoreline around Staten Island and hugging it until crossing the middle of the VZ. Newark normally clears me into the Bravo at 1400’ or 1500’ to fly up the corridor.

Pros:

- Better traffic Awareness

- No position reports

Cons:

- Flying slightly higher reduces the view

- If the controllers are busy, they may deny your request for advisories

- Can be intimidating to talk to NY Approach/ Newark/ LaGuardia

The other option is to fly in the VFR corridor. If you want to do it via this method there are just a few things you need to make sure you’re familiar with before you go. When in the VFR corridor you’ll need to make required position reports on a CTAF frequency. Make sure that you have the proper charts and have studied pictures of the landmarks so that you know what you’re looking for. I tend to plan on this as a backup in the event that the controllers won’t give me advisories.

Pros:

- Doesn’t require talking to controllers/ class B clearance

- More freedom to select altitude and routing as desired

Cons:

- Less traffic awareness

- Required position reporting

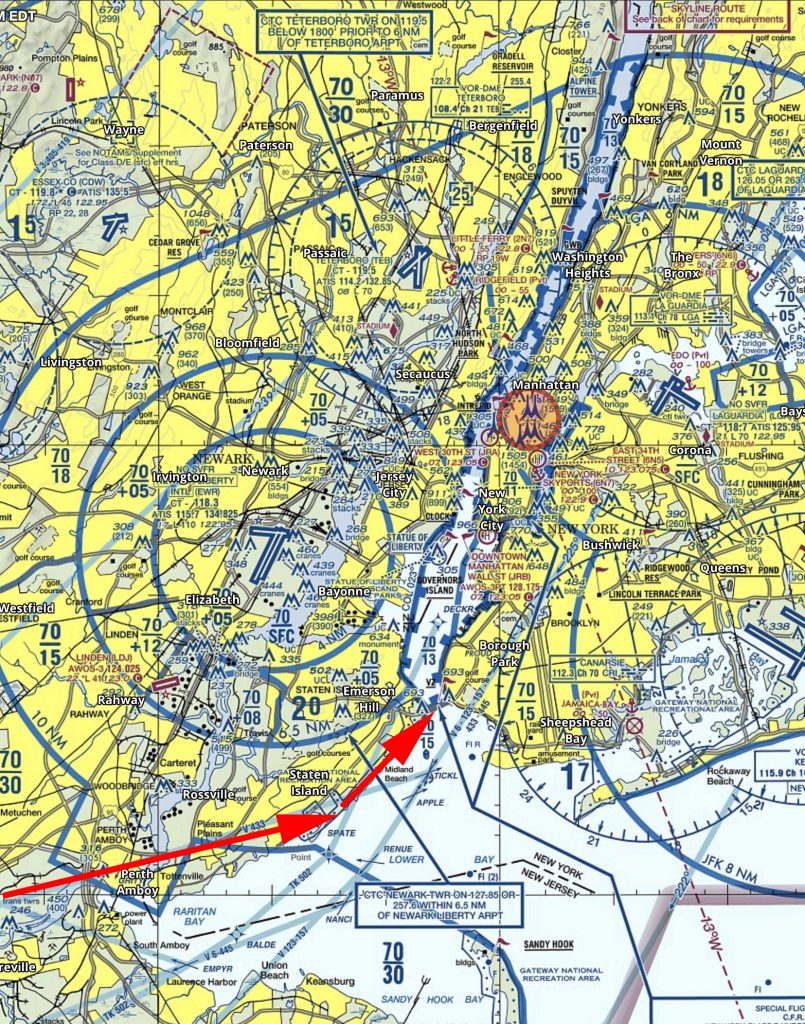

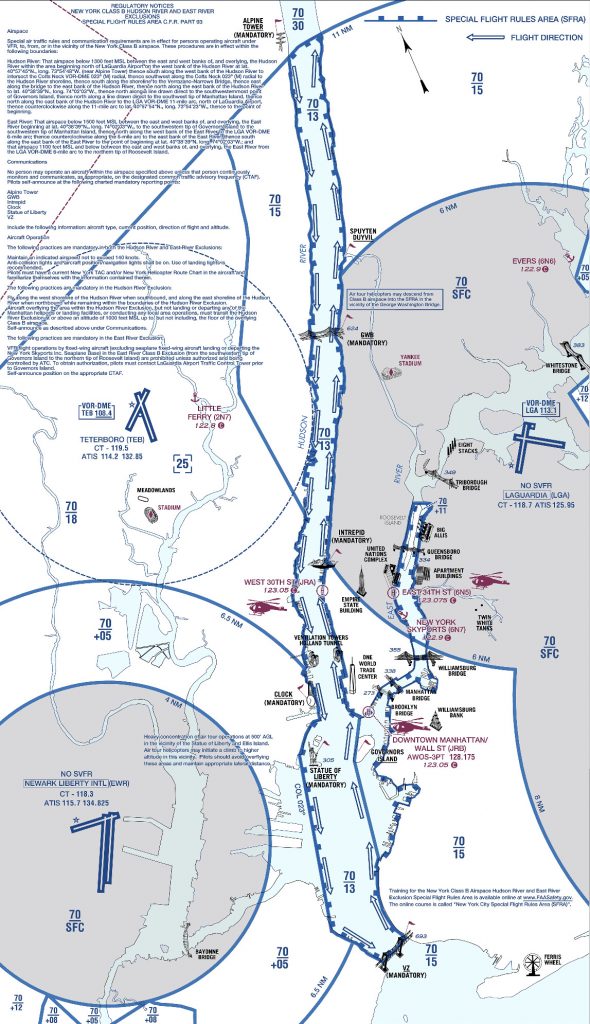

All the requirements and guidelines for flying the corridor can be found on the back of the NYC TAC chart. Any pilot flying the river is required to have one of these or a NYC helicopter route chart on board. If you’re using Foreflight, look in the Documents section under FAA Fly Charts and select the NYC TAC chart in order to read the back of page.

Below you’ll find examples of the diagrams/ instructions printed on the back of the NYC TAC charts.

You can see the traffic flow requires northbound airplanes to hug the east side of the river, while the southbound traffic stays on the west side. The VFR reporting positions (listed from North to South) are: Alpine Tower, George Washington Bridge, Intrepid aircraft carrier, Goldman Sachs (clock), Statue of Liberty, VZ (Verrazano Bridge). Each position report should include aircraft type, position, direction, and altitude.

Other things to be aware of:

NYC is always a hotspot for TFR’s. There are often TFR’s for baseball games or presidential movements so make sure to check before you head that way. Additionally, there is a speed restriction in place of 140 kts, though I’m not sure why anyone sightseeing would want to go that fast anyhow.

I realize that all of the procedures and restrictions can be overwhelming, but with the proper preparation, the Hudson Skyline is one of the most incredible places in the world to operate an airplane. There are a lot of things that are easy to get excited about that don’t live up to expectation, but this isn’t one of them. I’ve never taken anyone to the river that wasn’t impressed by what they saw and that’s why I plan to keep going back.