A few years ago I took off out of Chicago’s Dupage airport (KDPA) in a Bonanza headed for Deck Airport (9D4), a small uncontrolled airport about 60nm to the west of Philadelphia. It was late November and, unfortunately, due to some unexpected ice, I found myself flying a significant portion of the flight at 4-5,000 feet instead of the 11,000’ at which I had originally planned. This was an issue because I was burning significantly more fuel at 4,000’ than I would have at 11,000’. I did my fuel planning math and came to the conclusion that I would still make it to 9D4 with the required minimums. On I flew, watching the number on the totalizer decrease.

I arrived at 9D4 after dark. Although I didn’t think I would need one, I ended up having to fly an approach to get down below the cloud deck. My troubles weren’t over. After breaking out of the clouds, I was terrified to realize that the runway lights weren’t working.

Now, I had a problem. I was in a relatively unfamiliar area in marginal VFR at night and I was quickly running out of options as far as my fuel was concerned. Fortunately for me, 9D4 is located 14nm north of Lancaster Airport (KLNS), which is a towered airport with very nice approaches and facilities. Also working in my favor was the fact that Lancaster was reporting VFR. I headed as quickly as I could for Lancaster and landed uneventfully.

When I landed I had the required fuel minimums on the airplane, but I managed to scare myself pretty thoroughly. I realized that while I had been forced to deal with some unexpected complications: icing forcing me down several hours before my planned descent and inoperative runway lights that were not listed in the airport NOTAMs. I was very blessed that Lancaster was so close by and that I was able to land without having make an approach. Had LNS not been VFR, I could have easily burned through another 15 minutes of fuel maneuvering for and executing an approach. If, for some reason I’d had to go missed or perform a hold, I would have gone through my remaining fuel pretty quickly. To me, this is a classic example of “just because it’s legal, doesn’t mean it’s safe.” I realized I needed to change how I did my fuel planning.

Since then, I have enforced a personal minimum: 18 gallons must be on the Bonanza at the time I reach my destination. If things change un-expectedly enroute and I realize I won’t make it to my airport with at least 18 gallons, I stop. I had always tried to have an hour of fuel on board as a reserve, but having a hard number is an easy way for me to make decisions.

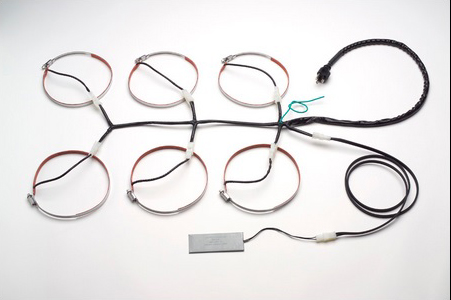

Having a fuel totalizer installed in an airplane is a really nice way to upgrade the panel and give the pilot a clearer idea of how much gas is being burned/ how much is remaining. The totalizer installed in our Bonanza is a JPI Fuel Flow 450. It has a lot of nice features which make fuel management chores much easier. If a totalizer is something that you are considering installing in your aircraft, or if you have one already, here are a few things that I’ve learned from my experience flying with them.

- The JPI 450 totalizer installed in the Bonanza (photo credit: www.jpinstruments.com)

- While helpful, don’t rely too heavily on the totalizer to do your fuel math for you. Similar to the negative effect that using GPS navigation can have on a pilot’s ability to navigate via a chart, over dependence on digital fuel systems can lead to problems. A fuel totalizer should be telling you what you already know, not doing all your math for you. Do your fuel math and confirm it with the totalizer. If it failed, you should still know how much you have and how much is needed.

- Likewise, don’t rely completely on the accuracy of a totalizer. Technology isn’t perfect, and if the instrument isn’t quite calibrated correctly, the numbers could be wrong. Fuel information is absolutely critical, and thus warrants constant monitoring and double checking. When you do arrive at your destination, keep track of how much fuel the airplane takes and compare it to the numbers on the totalizer to verify its accuracy.

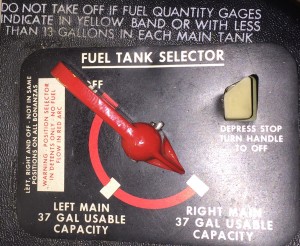

- Unless you are flying an airplane which has a “both” setting, you will still need to be keeping track of how much fuel is available in the aircraft’s individual tanks. For example: our Bonanza has two tanks, but the totalizer doesn’t keep track of that information. If I don’t remember to switch tanks, I can run one completely dry and the digital read out will indicate the remaining gas in the other tank. The totalizer won’t indicate anything about the individual tank quantity until the engine quits and the flow drops to zero.

Pictured below on the left is a fuel selector from a Piper Aerostar. The airplane has two selector valves and three fuel tanks. While the system is not difficult to use, it does require proper understanding and regular monitoring to ensure that the fuel is distributed correctly. The picture on the right is the selector out of an A36 Bonanza. I love the simplicity of the Bonanza’s fuel system, but it still takes attention and intention on the part of the pilot to keep track of how much gas is available on either side.

- The JPI unit that we have installed on our airplane even has an “hours and minutes remaining” screen as well as a “fuel required” screen. The totalizer actually talks to the GPS and is able to tell me how much gas I will need to get to my destination. Just remember that those numbers are computed only at the current flow and do not take into account the potential increases/ decreases in consumption which will occur as power settings are changed for descent and arrival into the airport. I may feel pretty good about my hours and minutes remaining when I’m sitting at 12,000 feet, but when center makes me descend to 5,000’ and I’m still an hour away from my destination, endurance will decrease. It also can’t take into account any additional flight time that may be required to shoot approaches, hold, or divert.

- Have you ever heard of “G.I.G.O?” It stands for “Garbage In, Garbage Out.” What it means is that the information which the fuel totalizer is giving the pilot is only as good as the information that the pilot gave it at the beginning of the flight. The totalizer in our Bonanza does not have any method of checking the quantity in the fuel tanks. At start up the pilot inputs the amount of fuel on board the airplane and the totalizer keeps track of how much is burned which is then subtracted from that inputted number. Ergo, if the amount of fuel is not updated or is incorrect, the fuel total numbers displayed will be inaccurate. If a pilot told the computer that the tanks had been topped off, but didn’t verify it, the fuel could be exhausted and the totalizer would still indicate that there was fuel available. It is, therefore, VERY IMPORTANT to confirm the airplane is fueled to the amount desired (visually if possible) and use the fuel gauges in the airplane to verify the accuracy of the totalizer.

- Use a timer: I like to use the timer on my phone to remind me when it is time to switch the fuel tanks. If I set the phone to vibrate and put it in my pocket, it will remind me to change tanks at the desired time if I haven’t remembered to otherwise. It’s also nice because I can write down exactly at what time (or quantity) I changed tanks so I can keep very accurate track of how much fuel I have in any given tank. This is especially helpful in airplanes that have more than two fuel tanks. Another option is setting the timer on a Garmin 430, 530, or G1000 to give an alert or message reminding the pilot to change tanks at a preset time.

It shouldn’t come as news to anyone that the importance of fuel planning cannot be overstated. I personally know multiple people who have run airplanes out of fuel because their planning wasn’t quite right or the weather changed and they were unwilling to take the time to stop. In the case of my Bonanza story earlier in this article, it was obvious to me before I even landed that I should have picked a fuel stop when it became apparent that I would arrive at my destination with less than my desired one hour margin.

The technology that we have now to help us keep track of our fuel usage is wonderful, but use it as an aid; not as your only source of fuel calculation. Remember to verify the amount of fuel on the airplane before you go because the number on the totalizer won’t mean anything if it doesn’t match the amount in the tanks! Above all, don’t be afraid to stop and get fuel when you need it. I’d rather have to tell the passengers that we need to stop for gas than deal with the potential consequences of running out.

Andrew Robinson is a 135 Charter Pilot and flight instructor who lives with his wife and 2 daughters in Pennsylvania. He flies Pilatus PC-12s and instructs in Beechcraft Bonanzas.