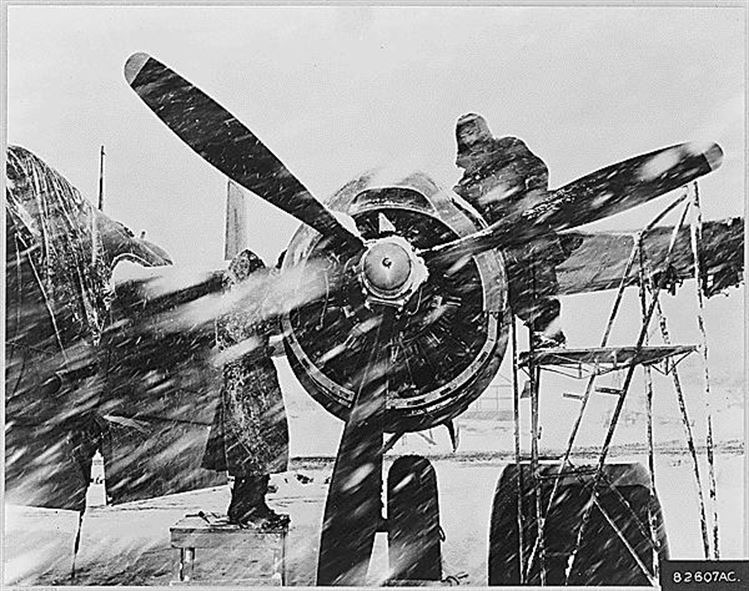

There are multiple ways to save money during the aircraft buying process. To start, since you are buying an airplane, you have some means of positive income in order to afford an airplane. Airplanes come in all different shapes and sizes and usually, an airplane can be found to fit almost any budget, whether is a $20,000 Texas Taildragger all the way up to a multi-million dollar jet.

One way is to stay within your budget. There will always be a shinier, newer, lower time airplane that is just above where you set your budget at. Don’t reach for it! There is a reason you set your budget where you did.

Another way is to shop around and get multiple insurance quotes. Your agent is in charge of engaging underwriters who are going to evaluate you and your airplane as risks, then price a policy accordingly. With most airplanes, you should get multiple quotes to see what fits you best. Beware though, because sometimes, you can get a lower rate, but it will require more training, so you end up shelling out more money in the long run. If you find a policy you like, but the training seems skewed or the liability isn’t high enough, you can always have your agent ask the underwriter to modify the quote. You are still in charge.

Finally, if you evaluate your mission and see that your budget can’t afford an airplane that carries enough or goes fast enough, look into taking on a partner or two to help with costs. Be thorough in vetting your potential partners as a good partnership is worth it’s weight in gold, but a bad one is downright unpleasant and often times hard to get out of. Find pilots who have the same mindset & personality you do and treat their stuff the same way you do. Try to take a ride in their car or go to their house, then you’ll see what kind of shape they will keep the airplane in.

The best way to cost yourself more money in the aircraft buying process?

Don’t do a pre-buy inspection.

A pre-buy inspection takes place after negotiations and once a Purchase Agreement is in place. You are pretty much set on the airplane, you just want a third party mechanic who is knowledgeable on that make and model of airplane (and this is a very important point) to go over it and make sure that it is sound from a mechanical standpoint. The buyer, you, want someone who has never had an association with the seller since the mechanic will be your representative in the process and you want him answering to you.

If you have used a broker or a buyer’s agent, that person should have already gone through the logbooks for you, so you’ll have a basic idea of the history of the airplane. However, knowledgeable mechanics find things all the time that turn out to be the responsibility of the seller to repair since it happened on their watch. Without a pre-buy, you would end up having to pay for that in the not to distant future.

Here is an example of where not doing a pre-buy can cost a lot of money.

An owner bought a late ’70s model Citation ISP, one of the very first Citations ever made. It had been based in Florida (salt & humidity + aircraft don’t mix well) for a while. The buyer didn’t use a broker, but thankfully had someone look through the maintenance history of the airplane. Since it was so old, the logbook reviewer didn’t have time to do anything but a basic overview, but he gave the thumbs up to the buyer.

The buyer decided he just wanted a boroscope inspection and the seller’s mechanics to look over the airplane. Remember what I said before about a third party mechanic? Well, these mechanics didn’t do a very thorough job. When the buyer took delivery of the plane, after about 10 hours of flying, he already had an $18,000-$25,000 maintenance bill.

You may say, well that’s a jet. Jet’s have specialized maintenance and need a more extensive pre-buy inspection.

On the contrary, in my 8 years in the training business, I have seen Cirrus, Piper PA46s, Bonanzas and several other piston engine airplanes that either didn’t have a pre-buy done or the pre-buy was done by someone who didn’t know that airframe. Lo and behold, things started breaking and adding up very quickly that would have been discovered on a good pre-buy inspection.

Don’t skip on the pre-buy inspection. They usually run a few thousand dollars, but save tons of money in the long run.