I’m surprised how often I’ve been asked about drones by concerned passengers as they load up for a charter flight. Most commonly I’m asked how many drones I’ve seen while I’m flying, or how many drones I’ve hit/ almost hit. Sadly, the media has made this drone crisis into something that it isn’t. I’ve never seen a drone while I was operating a full scale aircraft, and I’ve certainly never been put into a situation where I felt that a drone was a threat to my safety or the safety of the flight. In fact, I only personally know one pilot who has reportedly seen one around an airport and that was an isolated incident (and a non-event).

The reality is that while Unmanned Aerial Vehicles can be a real danger to full scale aircraft, incidents aren’t actually all that common and detailed information is often lacking or missing altogether. It is likely that some of the reported drone incidents were actually a case of a pilot confusing a loose balloon or a bird for a drone. This, combined with the media’s sensationalizing of every “close” encounter nationwide has led the public to believe that the problem is much bigger than it actually is.

In actuality, when the AMA (Academy of Model Aeronautics, the USA’s governing body for model aircraft) analyzed the data from the FAA’s 764 recorded Drone sightings, only 27 of them (3.5%) were actually recorded as “near misses” or “near collisions.” Additionally, only 10 of the records (1.3%) indicate that pilot was required to take evasive action.

The records also include reports of drone sightings at altitudes which would be impossible for civilian models to attain (19,000-24,000′). Finally, some of the sightings took place in areas which are specifically set aside for model aircraft and drones to operate. In those cases, the person flying the drone when it was reported was actually doing so in a safe and legal manner in an area designated for that specific purpose. If you’re interested, the whole article is available here and has a lot of great information.

As pilots, it is important that we do our part in helping reduce the risk of drone strikes. The biggest thing that we can do to help is to report any activity that we see so that it can be investigated and hopefully the drone operator can be found and dealt with. Try to get as much detail as possible about the incident, such as the size, color, location, direction and altitude of any sighted UAVs and report it to the closest tower or controlling agency.

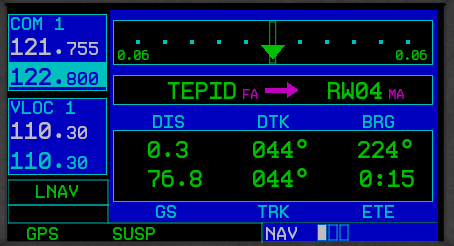

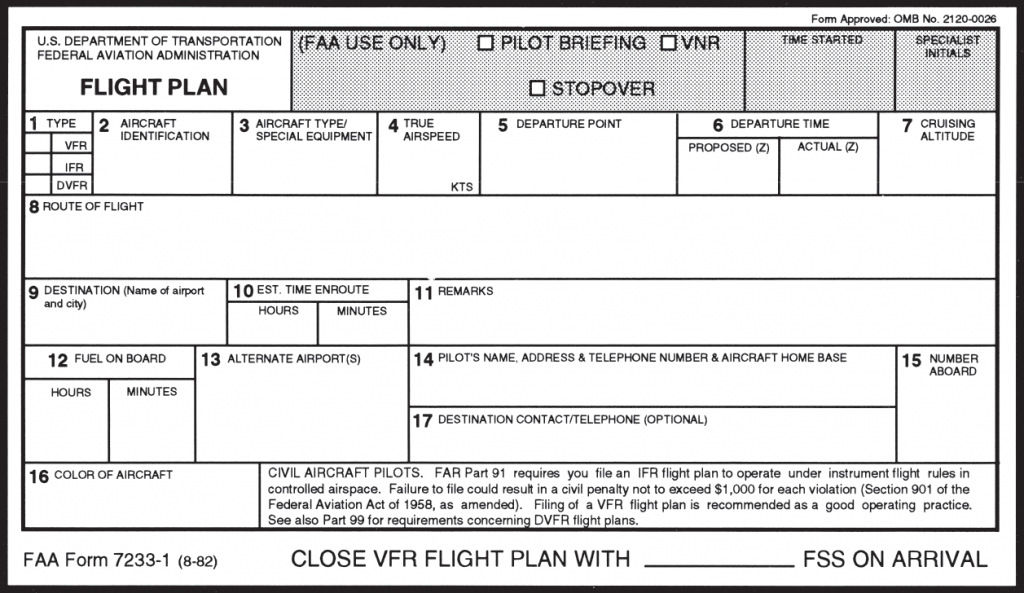

Recently, the people in Washington have come up with a bunch of new rules to regulate the operation of model aircraft. As of this year, every unmanned aerial vehicle between 0.5 and 55 lbs must be registered with the FAA and have an FAA issued registration number located on the model itself. The logic here is that if someone crashes a drone where it shouldn’t have been operated, the officials will be able to identify the owner of the model and take action.

Model manufacturers and vendors have also agreed to start providing information about a program called “Know Before You Fly” (KBYF) in the packaging of the drones. This program seeks to help educate new hobbyists to the rules and responsibilities associated with model aviation. For more information on KBYF, here is a link to their website.

In the end, the sad reality is that it’s a combination of many factors: new technology making models cheaper and easier to fly, GPS navigation and automation, the media blowing the incidents out of proportion, and inexperienced and foolish operators which have caused the growing concern and required the FAA’s action. I think that it is important to understand that thousands of people have been flying radio controlled models for many years responsibly and this has never been a problem. The AMA has rules (which are the same ones now adopted by the FAA) regarding flying location, altitudes, speeds, and more which have kept both the modelers on the ground and the pilots in the air safe until now. Its a classic case of a few foolish individuals who have caused all modelers to be cast in a bad light.

There is no reason to fly in fear, though. A pilot should always be watching for hazards as he or she is flying, regardless of the variety. In fact, according to the FAA’s website, there were 142,000 wild life STRIKES with civil aircraft in the USA between 1990 and 2013. That seems like a much bigger concern to me than the 764 reported drone SIGHTINGS. As with any new technology, drones are suffering from growing pains. As the rules fall into place and new operators become better experienced, hopefully we will hear about fewer incidents on the evening news. Anyway, I’ll stop “droning” on. Fly safe.

Andrew Robinson is a 135 Charter Pilot and flight instructor who lives with his wife and 2 daughters in Pennsylvania. He flies Pilatus PC-12s and instructs in Beechcraft Bonanzas.